If you grew up on a farm or spent lazy Sunday afternoons visiting your grandparents on theirs, you know the sound.

It springs from the fields: a sharply whistled, "bob, bob, whiiiiitttttteeeee."

The song of a Northern bobwhite quail is a part of our collective memory, what the French philosopher Maurice Halbwachs termed "la mémoire collective." Along with the taste of fresh lemonade and newly ripened watermelon warm from the garden, many of us seem to share this memory, or something like it.

We also seem to remember the bobwhite's exuberant call, but few of us have ever actually seen one.

And, its getting harder to do just that! In 2007, the Audubon Society released a list of the 20 Common Bird Species in Decline. Complied from 40 years of data, the number one bird on the list was the bobwhite. The meadow loving gamebird has suffered a shocking 82 percent decline in overall population in the past four decades.

Why?

As the Audubon article penned by Greg Butcher states,"The loss of suitable bobwhite habitat—from large-scale agriculture, intensive pine-plantation forestry, and development—is the most dominant threat to the long-term survival of these common grassland birds. Losses to nest predators, and even fire ants—competing for food, attacking nests, and prompting humans to spray pesticides—also seem to be contributing to the bobwhite's decline."

|

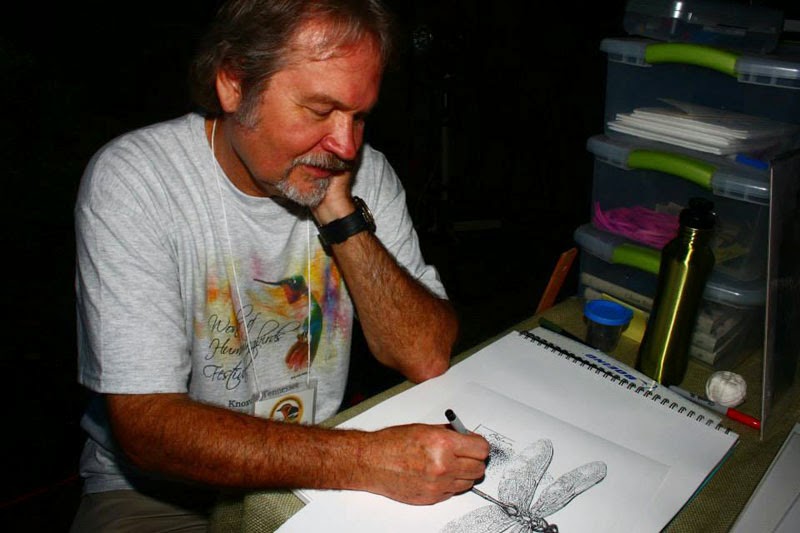

| Documenting the documentor: Kristy photographing the bobwhite |

But there it was, wayward, at the Lower Overlook on the Homesite; more or less at the edge of the forest walking along a trail just like any other Saturday afternoon visitor.

Way to go Kristy for having the acumen to know that it was a very odd bird way out of place!

- Photos by Kristy Keel.

•